FR3 band

Opening the FR3 Band: opportunities and challenges

Discovering the potential of this band for the future of wireless communications

by Irene de Gruijter

February 18, 2025 in News

It’s no surprise to hear about the potential capabilities of the FR3 band in the new generation of wireless communications. The rapid growth in network traffic and data rates brings an increasing bandwidth demand (nothing that we haven’t heard either!). All this shifts the focus to other, less-used frequency bands like the FR3 band. This band covers the frequencies of approximately from 7 to 24 GHz and promises to end the current problems in 5G communications.

In this article, we’ll explore the promises of the FR3 band, positioning itself as a key player in the transition to 6G. We will also cover the main challenges of implementing it and explain why relying on FR1 and FR2 alone won’t be enough for the future of wireless communications.

So, what is the FR3 band exactly?

Also called the “upper-mid band” in the mobile communication industry, it is the frequency band that specifically covers the range from 7.125 GHz to 24.25 GHz. This band lies between FR1 (also known as sub-6 GHz) and FR2 (commonly referred to as mmWave). [1],[2]

As of today, part of the FR3 spectrum is allocated to satellite internet and military communications. It is said to be one of the main band candidates for the next-generation 6G communication system, as it is barely used in 5G. Nevertheless, countries will have to coordinate their use of these frequencies for different applications in order to allow new opportunities to appear in this band. [3],[4]

It also has been identified as the new frequency spectrum that combines the advantages of the adjacent bands (FR1 and FR2) while minimizing their drawbacks, and this is a significant point to rely on. According to [5], the FR3 band will enable high-speed data transmission (a feature of FR2) while improving propagation characteristics (a feature of FR1), especially in urban environments. This potential « discovery » does not come without challenges. While it is true that features of FR1 and FR2 could be combined, their drawbacks must be avoided. To benefit from the FR3 band, regulatory frameworks, together with the scientific community, must adapt to accommodate its use. [6]

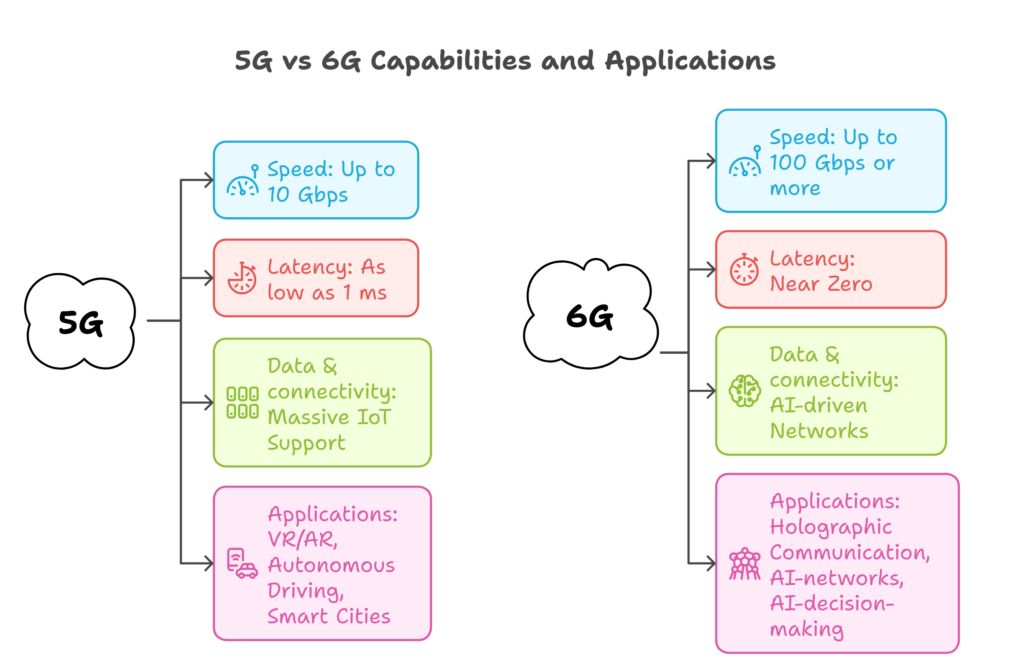

On a brighter note, the FR3 band is set to be a game-changer in the transition from 5G to 6G. 6G aims to provide faster speeds, ultra-low latency, and more reliable connectivity than ever before, and it is said that its commercialization is expected to be around 2030. [7] So there is time.

Why this band?

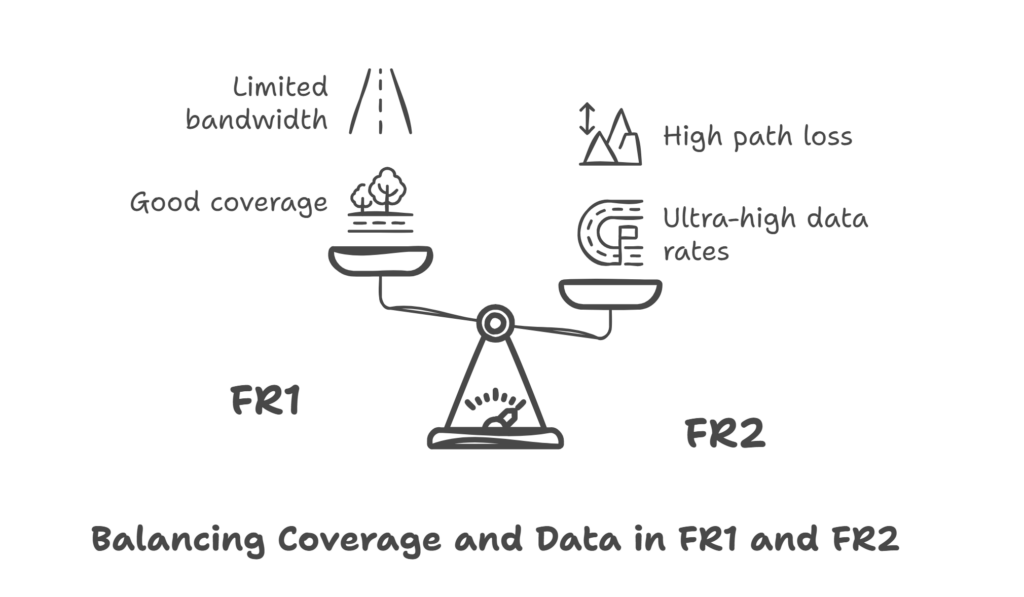

Let’s introduce some historical background. Both FR1 and FR2 bands have been the primary focus of 5G research and development: FR1 (450 MHz–7.125 GHz) is capable of delivering broad network coverage and penetration, and FR2 (24 GHz–71 GHz) offers very high data rates in large bandwidths. In layman’s terms, they have been used in 5G because they provide a good balance between coverage, capacity, and spectral efficiency (how much data fits in a given bandwidth). However, they both have their own drawbacks: FR1 is known to have limited available bandwidth (typically 100 MHz per channel), and signals in FR2 suffer from high path loss and require dense small-cell deployments (small-cell = low power base stations).

The limited bandwidth issue in FR1 comes from the fact that most of its frequency bands were originally allocated for earlier cellular technologies (like 4G LTE), where bandwidth needs were lower [8] [9]. This limitation means that FR1 struggles to support very high data rates, making it less ideal for ultra-fast 5G applications compared to FR2 or future FR3 bands. On the other side, the reason why the signals in FR2 suffer from high path loss is that higher frequencies have shorter ranges and weaker penetration; placing more small cells that maintain good coverage plus connectivity would be a viable solution. [10]

Having said that, the response to the initial question is quite straightforward: The need for more bandwidth due to the increasing amount of data needed today will be addressed with the arrival of 6G. (To give a rough idea, the latest Ericsson Mobility Report states that the monthly data traffic per smartphone in North America has increased by +54% from 2021 to 2022: from 13 GB to 20 GB, and is expected to triple to 58 GB by 2028.) [11]

As mentioned in the introduction, 6G will be a step beyond 5G, providing faster speeds and better connectivity, and the use of the FR3 band will help achieve that [5]. This, without a doubt, will lead to a “telecom industry re-evaluation,” as Margo Anderson suggests in her November 2024 article [12].

Advantages of the FR3 band

There is a superb article that details the immense potential of the FR3 band in 6G wireless communications. It was written by Zhuangzhuang Cui, Peize Zhang, and Sofie Pollin last year under the European iSEE-6G SNS-JU project, which aims to study UAVs (unmanned aerial vehicles = drones) and air routes under 6G. I strongly recommend it, as it includes a comprehensive study from almost every point of view (of wireless communications), from a state-of-the-art industry and academia to simulations to prove the different benefits of this FR when compared to others. [5]

The goal of this article is not to take credit for their contributions but rather to highlight them and try to explain the most relevant ones in a vulgarized manner.

A logical starting point for an article listing the main opportunities of the FR3 band would be to divide the advantages into three categories: coverage, flexibility, and functionality.

From a coverage point of view, it should now be noted that in general, higher frequencies offer more bandwidth but less coverage, while lower frequencies provide better coverage but less capacity. This makes deploying networks expensive, as both low and high frequencies are needed for indoor and outdoor use. The implementation of FR3 (7-24 GHz) solves this by balancing coverage and bandwidth, making it ideal for “continuous indoor-outdoor” connectivity, as they state. It also supports massive antennas for 3D beamforming (supporting vertical users as UAVs, the target use case of this paper). [5]

Now, talking from a flexibility perspective: According to [13], implementing massive MIMO (with over 256 antennas) in the FR3 band can significantly enhance network capacity and performance. This presents a solution for the high demands of data rates. anticipated in 6G communications. This also aligns with the fact that placing massive MIMO arrays in FR1 is impractical due to their large size and weight (and other deployment constraints). Meanwhile, FR2 struggles with poor propagation conditions and costly beamforming. FR3, however, strikes the right balance—its centimeter wavelength allows for more antenna elements. As the number of antennas increases, the channel becomes more stable and predictable (aka channel hardening). This results in more consistent performance and improved spatial multiplexing (serving multiple users at once), making it a much more flexible solution than when using FR1 or FR2 bands. [5]

As far as the different functionalities of the FR3 band are concerned, it is relevant to bring ISAC (Integrated Sensing and Communication) into the discussion. Since 6G networks are evolving from pure communication services to multi-service applications, new technologies such as ISAC come into play. For those unfamiliar with the term, ISAC is a 6G technology that combines wireless communication with radar-like sensing in the same network. Simply put, ISAC transmits data like a regular network while simultaneously detecting objects, motion, and environment (like a radar). Today, there are existing radar technologies in X (8 to 12 GHz), Ku (12 to 18 GHz), and K (18 to 27 GHz) bands that offer a solid foundation for ISAC development. However, developing multi-band ISAC in FR1 and FR2 bands is not such an easy task (mainly due to the big difference in frequency and bandwidth ranges) [14]. As a response to this, FR3 provides a middle ground, providing the right conditions for reliable sensing and communication in one system. [5]

Use cases

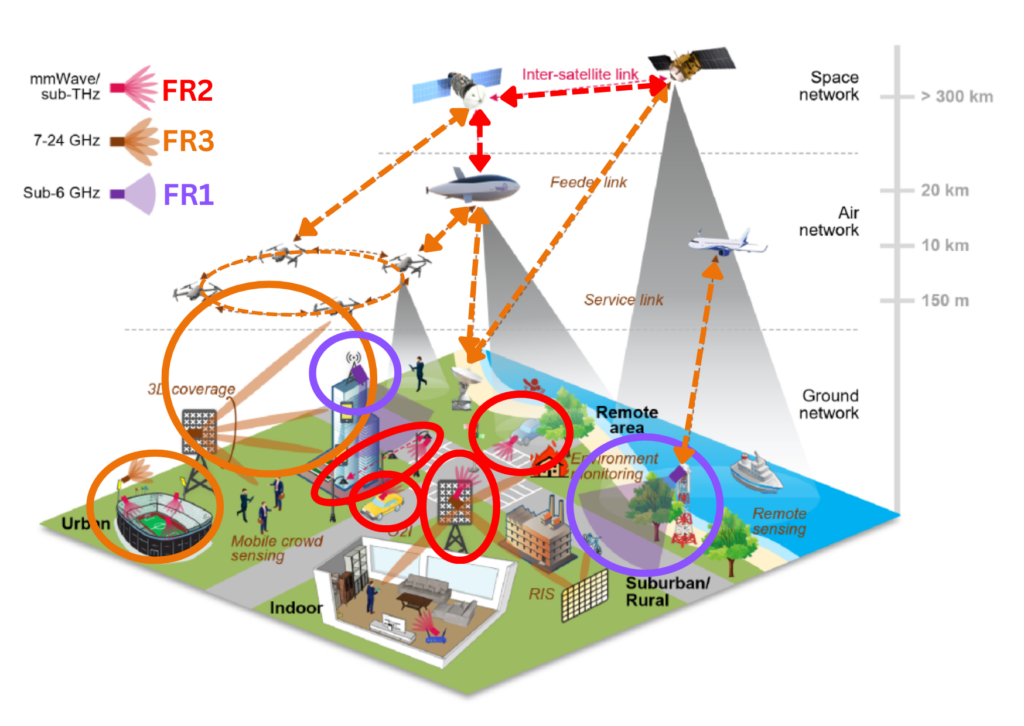

To better visualize the possible use cases in this band, the same article provides the figure below. This image takes into account the existing FR1 and FR2 bands (sub-6GHz and mmWave/sub-THz, respectively), categorizing the use of each depending on the distance. It concludes that FR3, represented in orange, is ideal for medium-range areas like cities, factories, and places with both indoor and outdoor coverage [15]. On the other hand, FR1, in purple, is better for rural and remote areas, while FR2, in red, is more suited for tasks like backhaul, cars, and hot spots. This shows that FR3 can cover a wider range of uses, while FR1 and FR2 are more specialized for specific scenarios. [5]

There are more specific use cases that are emerging and are driven by the latest regulations, technologies, and trends. Hot topics like NTN’s (non-terrestrial networks) or RIS (reconfigurable intelligent surfaces) are eventually gaining more and more attention. However, in an attempt to leave this article somehow concise, these topics will be discussed in a separate post.

Challenges

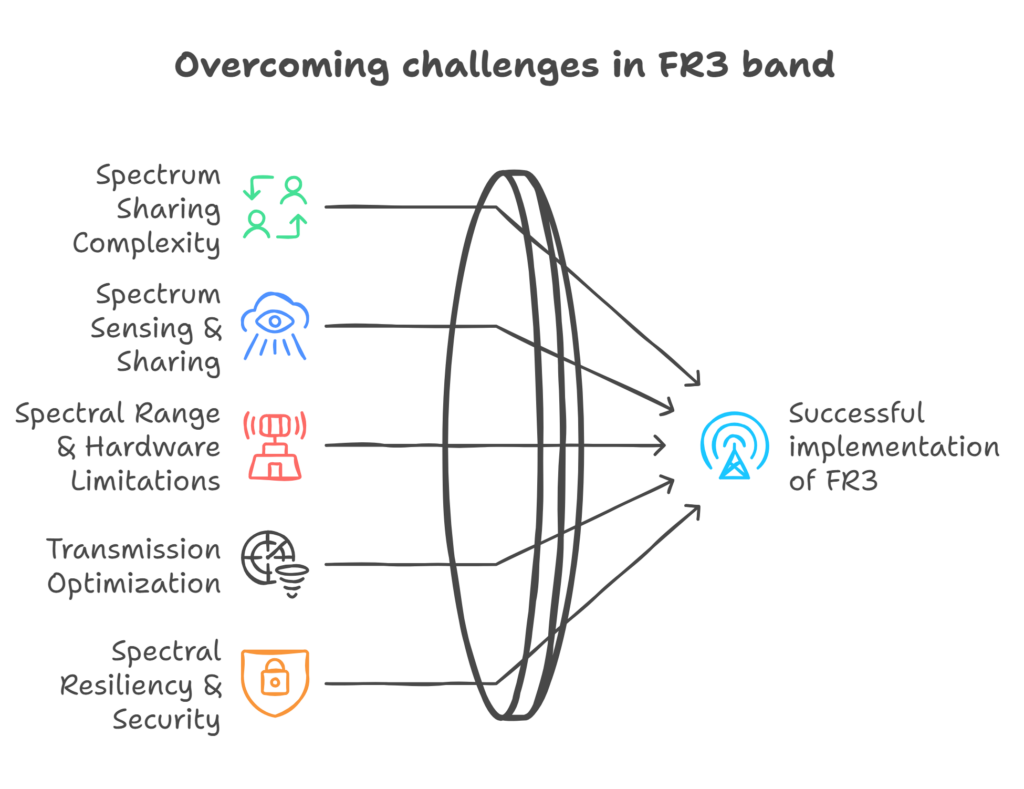

It goes without saying that there are several challenges with the implementation of the FR3 band. Having spoken about the bright side of the FR3 band, many questions remain unanswered. For instance, “What technological advancements will be required to make the most of the FR3 band for 6G communications?“ or “How will the FR3 band be allocated among different applications while avoiding interference with existing services? ». This section aims to respond to these questions as well as the general challenges that this band presents.

In January 2023, the « Upper Midband Software Defined Radio Workshop Report » [6] highlighted the importance of technological and policy advancements for the effective use of the FR3 band over the next decade. The report acknowledged that, while reasonably wide, the FR3 band will likely be shared due to the large number of users. Paolo Testolina, a postdoctoral research fellow at Northeastern University’s Institute for the Wireless IoT (Internet of Things), agrees with this statement in the article, stating that “spectrum sharing will be key in this band.” [4]

But what do we mean by this?

Sharing the spectrum means that different users, services, or technologies will need to share the available frequency spectrum to maximize its usage while avoiding interference. Traditionally, a frequency band is exclusively assigned to a single operator or service. Spectrum sharing allows multiple entities to coexist in the same band, improving efficiency and flexibility. The Federal Communications Commission Technical Advisory Committee (FCC TAC) has a paper that gathers the current allocations and uses in the 7.125–24 GHz band, both for the US case and the rest of the world. [16] Together with their 6G working paper [17], they emphasize that it is indeed necessary to use segments of the FR3 band if we want to cover the increasing demands for data. The problem is that some of these segments are already in use (as mentioned before, parts of the FR3 band are used by satellite internet and military communications). There are different mechanisms to share the spectrum, namely licensed spectrum access (LSA) or dynamic spectrum sharing (DSA). However, rather than diving into the details of each, the key takeaway is that multiple different actors will need to share the spectrum when implementing the FR3.

The authors in [14] very well detail the main challenges when deploying cellular networks in this band, including spectrum sharing. This work presents a highly valuable contribution to the studies of the FR3 band, and the challenges proposed next will be based on their contributions.

With spectrum sharing comes the prior step of spectrum sensing. This is detecting who is using the spectrum. Unlike mmWave (FR2), where the spectrum was largely unoccupied before deployment, some users occupy parts of the FR3 band today (again, by satellite internet and military communications). This makes spectrum coexistence a major challenge, requiring advanced sensing mechanisms to detect and avoid interferences.

FR3 occupies a broad frequency range (unlike traditional cellular bands that cover only a small percentage of the carrier frequency). According to [14], another major challenge is to adapt the current RF Front ends so that they are capable of sensing and dynamically exploiting large bandwidths while optimizing directional transmissions (adjusting the transmission of a signal to improve its tx-rx performance)

They also state that given the shared nature of FR3, protection against jammers and signal disruption is crucial. Techniques mentioned before, such as advanced sensing, or others, such as spatial adaptability, will be key in ensuring reliable communications, particularly for critical 6G infrastructure. [14]

Conclusions

The FR3 band is expected to play an important role in the future of wireless communications. Sitting right between FR1 and FR2, it brings the best of both worlds—higher speeds and better coverage—making it a strong candidate for the next generation of mobile networks. But as exciting as it sounds, it’s not as simple as it seems.

On the technical side, adapted RF front ends, better spectrum sensing, and solutions for interference management will be needed. On the regulatory side, governments and industries will have to figure out how to share and allocate this spectrum without disrupting existing services. With growing demands for data and emerging technologies like ISAC and UAV communications, tackling these challenges becomes a hot topic today.

That being said, FR3 is more than just another frequency band—it’s a real opportunity to rethink how we build future networks. The pieces are coming together, and with the right efforts from researchers, policymakers, and industry leaders, this band could be a game-changer for 6G and beyond.

Thank you for reading!

References

- Smee, J. E. (2022, February 10). 10 innovation areas for 5G advanced and beyond. Qualcomm. https://www.qualcomm.com/news/onq/2022/02/10-innovation-areas-5g-advanced-and-beyond

- Next G Alliance. (2022, May). 6G spectrum research areas. https://cdn.codeground.org/nsr/downloads/researchareas/2022May_6G_Spectrum.pdf

- Everything RF. (n.d.). FR3 frequency bands. https://www.everythingrf.com/community/fr3-frequency-bands

- Anderson, M. (2024, November). 6G spectrum and FR3. IEEE Spectrum. https://spectrum.ieee.org/6g-spectrum-fr3

- Cui, Z., Zhang, P., & Pollin, S. (2024). 6G wireless communications in 7–24 GHz band: Opportunities, techniques, and challenges. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.06425

- Wireless Institute at Notre Dame. (2024, January). Upper mid-band SDR workshop report. https://wireless.nd.edu/content/uploads/2024/01/Upper-Midband-SDR-Workshop-Report-9.11.23-1.pdf

- Orbis Systems. (n.d.). 6G challenges for radio testing. https://www.orbissystems.eu/en/resources/blogs/6g-challenges-for-radio-testing/

- Science Media Hub. (n.d.). 5G map. https://map.sciencemediahub.eu/5g#p=14

- ShareTechnote. (n.d.). 5G FR bandwidth. https://www.sharetechnote.com/html/5G/5G_FR_Bandwidth.html

- Wikipedia. (n.d.). 5G NR frequency bands. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/5G_NR_frequency_bands

- Ericsson. (2024, November). Ericsson mobility report. https://www.ericsson.com/en/reports-and-papers/mobility-report/reports/november-2024

- Anderson, M. (2024, November). 6G spectrum and FR3. IEEE Spectrum. https://spectrum.ieee.org/6g-spectrum-fr3

- Cui, Z., Zhang, P., & Pollin, S. (2024). 6G wireless communications in 7–24 GHz band: Opportunities, techniques, and challenges. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.06425

- Kang, S., Mezzavilla, M., Rangan, S., Madanayake, A., Venkatakrishnan, S. B., Hellbourg, G., Ghosh, M., Rahmani, H., & Dhananjay, A. (2023). Cellular wireless networks in the upper mid-band. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2309.03038

- Nokia. (n.d.). Extreme massive MIMO for macro cell capacity boost in 5G-Advanced and 6G. https://onestore.nokia.com/asset/210786

- Federal Communications Commission (FCC). (n.d.). Spectrum sharing report for TAC. https://www.fcc.gov/sites/default/files/SpectrumSharingReportforTAC

- Federal Communications Commission (FCC). (n.d.). Updated spectrum sharing report for TAC. https://www.fcc.gov/sites/default/files/SpectrumSharingReportforTAC%20%28updated%29.pdf